By Veronica Penney

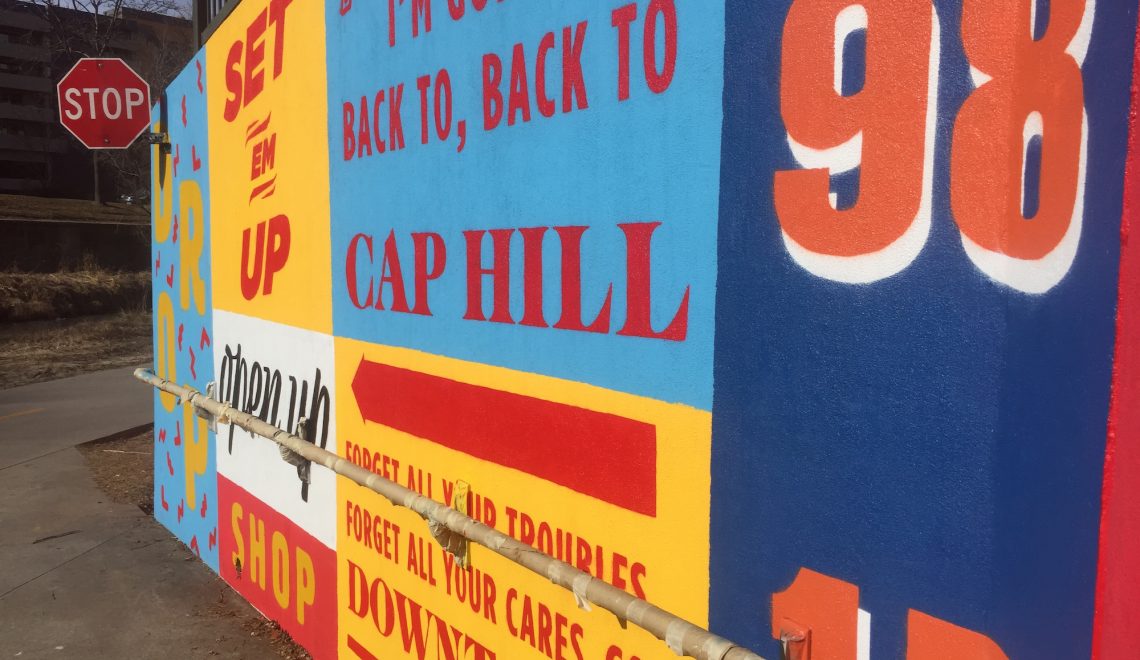

If you’ve found yourself on Denver’s Cherry Creek Trail recently, chances are that you noticed artists painting new murals on the retaining walls along the path.

The murals are part of the City of Denver’s Urban Arts Fund initiative, which sponsors artists to create murals in public spaces around the city. The aim is to use community art to turn “dilapidated areas into well-tended and active community gathering spaces.”

According to Tariana Navas, Director of Cultural Affairs, the Urban Arts Fund has facilitated close to 150 murals throughout Denver. The Urban Arts Fund teamed up with the Denver Partners Against Graffiti to measure graffiti reduction and found that the program abated roughly 20,000 square feet of wall space from vandalism. Data on the square footage of walls cleaned and money spent on cleanup helps the Urban Arts Fund identify the areas of the city that need attention.

Though the Cherry Creek Trail is a popular route for bike commuters and joggers, parts of the path can seem run-down or neglected. The Urban Arts Fund hopes to brighten these spaces through their work.

“It’s integrating art into our daily life,” says Navas. “Especially in the trail, when sometimes people feel that it’s not the safest space, it definitely activates it more. It makes a space where people want to be.”

In addition to brightening public spaces, murals and public art can play an important role in graffiti prevention. For a graffiti artist, a whitewashed wall can be like a blank canvas waiting to be tagged. Navas notes that it is less common for a mural to be tagged by graffiti.

“There are places that are tagged, but there is kind of an artist’s code in terms of graffiti art that if a graffiti artist does a mural, that’s not tagged,” says Navas.

In 2007, Barth Quenzer noticed a similar phenomenon while working at Brown Elementary as an art teacher. The retaining wall surrounding the school would be tagged with graffiti, whitewashed, and tagged again on a weekly basis.

Image: Barth Quenzer

Quenzer and his students began considering what they, as artists, could do to help prevent the graffiti tags appearing on school property. Barth formed an after-school mural club to create a mural for the retaining wall.

“The mural actually had an impact on that pattern of tagging on that wall. We didn’t see any more tagging in that location, and that was an interesting phenomenon because we assumed potentially, that mural would be tagged on just as the blank wall had been,” says Quenzer.

The Urban Arts Fund now incorporates a more formal youth development component, allowing students to work with local graffiti artists. Students can participate in the brainstorming and design process, then put paint to the wall under the direction of experienced graffiti and street artists.

Image: Barth Quenzer

According to Navas, involving the community in the creation of a mural is key.

“When you bring artists into a neighborhood and you bring youth into that process, that process of community building and building pride in beautifying your neighborhood is as valuable as the final result of a beautiful mural,” says Navas.

“If you actually invest in bringing arts and culture into your neighborhoods, it’s much more than the arts. It’s directly tied to quality of life, it’s directly tied to community building and how you’re supporting local talent, it’s directly tied to youth development,” says Navas. “It’s that involvement of community and engagement in creating pride where you live and play.”

Head to the Urban Arts Fund website to find their map of Denver murals and learn more about their projects.