Experts and politicians alike have argued for years about reforming the U.S. prison system, especially in light of the fact that we have the highest prison population rate in the world. But one piece of the puzzle tends to be forgotten: recidivism.

Defined by the National Institute of Justice as “a person’s relapse into criminal behavior, often after the person receives sanctions or undergoes intervention for a previous crime,” recidivism is a glaring issue. In fact, one study found that within three years of release, about two-thirds of released prisoners were rearrested.

Thankfully, several programs across the country are doing something about this problem, and it looks like Denver soon may be the newest destination for an initiative in that same vein. Back in December, Denver City Councilman Albus Brooks and several Denver natives, including former gang members, visited the various social enterprises of Los Angeles’ Homeboy Industries, the nationally renowned gang rehabilitation program, for the purpose of garnering ideas for a similar program.

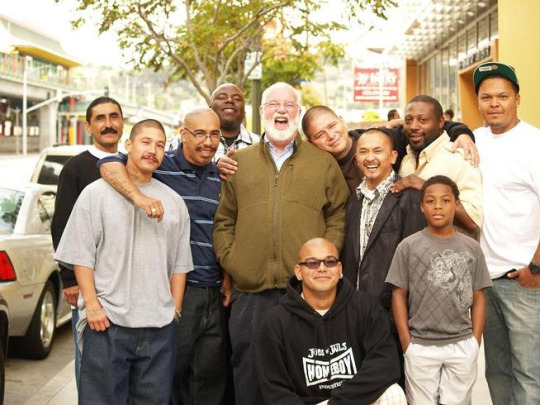

Recognized as the largest and most successful gang intervention and reentry program in the world, Homeboy was founded in 1988 by Father Greg Boyle and currently works with over 10,000 former gang members each year, offering them full-time employment, tattoo removal, job training, education, legal help and counseling. What started with a bakery that employed the previously incarcerated people has grown into a range of nonprofits that train and employ ex-gang members.

Lamumba Sayers, one of the men who toured Homeboy Industries, expressed his belief that such a program could change lives based on his experience of employing childhood friends and reformed gang members in his moving company. “If you put the right opportunities in place, people will follow. If people have the job opportunities, where they can learn what it’s like to be a business owner, it can change everything.”

The city-funded visit is particularly timely on multiple levels. For one, 2015 saw a sharp rise in violent crime in Denver, mostly attributed to gang violence, which drove a police crackdown on gangs. “We’ve invested a lot of money in policing up, but not a lot of money in creating economic opportunities,” Councilman Brooks said. “We really need to look at appreciative ways we can get these folks gainfully employed and back into society and back into the success Denver is seeing right now.”

The visit is also well-timed on a national level considering the fact that criminal justice reform has been in the spotlight this year. After all, President Obama pushed for major reform after a historic visit to a federal prison back in July and commuted the prison sentences of 46 non-violent drug offenders. And after he toured a drug treatment center and met with ex-convicts in Newark, N.J. in November, he continued to take steps to help former inmates secure jobs and homes. He also met with Father Boyle and former gang members last year.

Moreover, due to federal changes to drug sentences in the coming year, thousands of nonviolent drug offenders will start to be released early. As a result, strategies need to be set in place to help these former inmates reintegrate into society. A program like Homeboy Industries could also help young adults hoping to turn their lives around before ending up in prison; in effect, by creating jobs, the initiative could ultimately help end youth violence.

However, as Haroun Cowans, an entrepreneur and executive director of the Impact Empowerment Group who also joined the tour, points out, the jobs can’t just be menial and low-paying—there needs to be an element of empowerment. “We need to think about how we can get folks in the community to be able to participate in this economy in a positive way and give them goals that could really empower them,” he said. “We want them to see themselves as a part of this prosperity and giving back to the community. It’s not just giving them a job but empowering them to be able to employ others like themselves.”

Homeboy Industries seems like a great model from which these goals can be realized. In addition to hosting government and community leaders seeking to mirror Homeboy’s endeavors, last year the organization formalized Global Homeboy Network, an international group of similar organizations that originated from visits to the L.A. facility. “We know Homeboy will never be the McDonald’s of gang-intervention programs,” said Homeboy Industries spokeswoman Alison Camacho. “What we consistently do is take the opportunity to share our model concretely, and we spend a great deal of time helping other organizations get off the ground.”